People of Kashmir are fed up with corruption, favoritism, and nepotism. They want an end to this tumult and are willing to come forward to whistle blow the corrupt. She wants the politicians to now start preparing for a free and fair election in the erstwhile state. A new wave of young activist politicians is now ready to jump into making sure that legislation works for their people. She argues that the old Kashmir’s ethos remains.

Meera Kaul

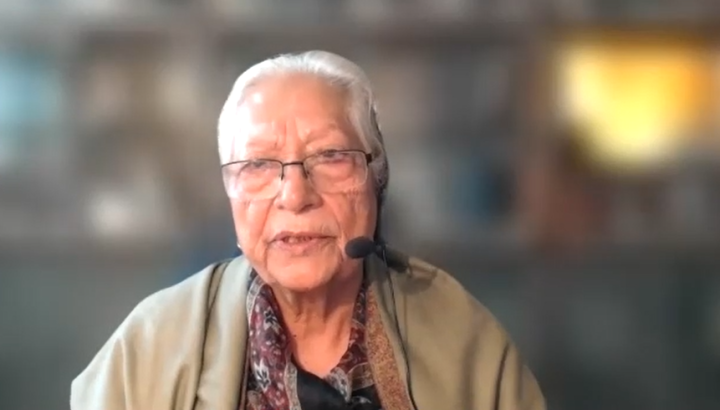

As a child growing up in Kashmir, women in power, working with men and being equal was a norm for me. A lot of this normal was because of the non-conformist familial values that I was brought up with. It was normal for women in my family to not be engaged in gendered roles. I was indeed fortunate to grow up watching my aunts, my cousins, my siblings living their lives to their real potential. My aunt Khem Lata Wakhlu – a social activist and a maverick thought leader — was one such role model. Kashmiri pandits have been at the center of intellectual and artistic movements over the centuries and Khem Lata Wakhlu simply continued those great traditions.

Khem Lata Wakhlu started her political career in the early 1970’s when she and her husband — a Commonwealth scholar — returned from the United Kingdom. It was a defining move by a woman whose strength was her husband and family. Not only did they encourage her, but they also helped her in her path to political prominence. In Kashmir, she was surrounded by quite a few women in the family who were passionate about education. After their return from the United Kingdom, she and her husband decided that she should contest elections in Kashmir. Her biggest cheer leader was her husband — Dr. O N Wakhlu. With his support and that of her family, she was able to become a career politician. She fondly remembers how the neighbors, friends and family all came together to support her. Of course, there were a few naysayers who had things to say about how as a woman candidate she was bringing shame to her family and the Kashmiri pandit community, yet none of them had the courage to say that to her face. The first election she contested was in 1971.

Khem Lata Wakhlu had a dream of building a society for which Kashmir was known for centuries. In A Kashmiri Century, she tells us the stories that explain the ethos of the Kashmir of her dreams. In this riveting narrative of family, love, relationships, and community in Kashmir — spread over generations — she explores the ethos that makes Kashmir and Kashmiris special. It was the politics that connected her directly with the people of the valley. After her debut as an independent politician, she joined the ruling National Conference — the party of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah. Sheikh Abdullah had just rejoined the political center stage after many years out of the limelight. This gave her the opportunity to travel all over the state — even to remote places — and get to know the state of the people of both prominent religions intimately. She developed insight about their lives, priorities, and their communities. She was able to understand the ethos of these old communities. She could clearly follow the changes in the Kashmiri society from those times and the process of indoctrination over the years. She wrote it all down. Her love for writing is a combination of natural acumen and encouragement from her father and then husband who would inspire her to write to him to communicate even when they had their little tiffs.

A Kashmiri Century is a fresh look at Kashmir that was. She narrates in these thirteen stories of how families who migrated to other parts of India would abduct well-born Kashmiri children to continue their Kashmiri lineage. You may get transported to the times when Kashmir was a plural society, rich in education, with its own sub-culture of traditions, caste, bloodlines, and the politics of Kashmiri familial relationships. A very typical of the Kashmiri way of doing things. The anecdotes tell the story of families, their culture, their idiosyncrasies, their habits, their behaviors passed down to each generation, their customs, their deeper significance, their joys, and their disappointments. Regardless of the religious affiliation, these could have been taken from the files of any family with lineage in the valley. All these little stories make Kashmir look special.

The opening story is of her grandfather’s brother, who was abducted by a noble Kashmiri lady called Mrs. Sumali Kaul, then living in Lucknow. Her great grandfather Kashi Nath and a few family elders undertook the journey from Srinagar to Lucknow — which took a couple of months in those times — to retrieve the child. Upon reaching the Kashmiri Mohalla in Lucknow, they approached a Kashmiri elder of the community knowing well that asking for such an urgent meeting would accentuate the urgency of their mission to retrieve their abducted child. This matter was one of concern to the community as it had the potential of opening the entire Kashmiri community in Lucknow and elsewhere in India to devastating criticism, giving the community a bad name.

Ultimately, the Kashmiri Sabha (community) got involved in this sensitive matter. The Sabha opinion makers were divided into two groups. One, quite certain that the future of the abducted child was secure in Lucknow with the assurance of modern education. The other held the view that the child needs to be with his biological parents, and it was upto them to decide how and where he should live. Kashi Nath had never seen a more charming, vivacious, and bolder woman than Sumali Kaul. The bigger shocker was that the child had grown attached to his new environment and did not even respond to his father’s loving embrace. Kashi Nath had in fact abandoned his wife Heemal and lived a carefree life in the progressive Lucknow society with Mrs. Kaul. Till the family decided to send his wife Heemal to Lucknow as well and — as things settled in — the abducted child, his older brother, the kidnapper, and the great grandparents all created an environment for the children to get the best of education and exposure.

These stories articulate the composition of the Kashmiri society and its reformism, the fads and the taboos, the societal fabric and the transgressions. The book is a Kashmiri granny story treasure — one where your grandparents tell you about what your ancestors did and how the life in their times was. Anecdotal Kashmir documentation begins with the stories of arrival of Shah Mir who spread Islam in Kashmir in 1339 CE and then jump to the times when the Kashmiris started the period of disconcert with their political situation. The stories of Kashmir in the intermittent period need to be told too. This book just purports to achieve that.

Khem Lata squarely lays the responsibility for the indoctrination of the valley on “outside forces and petro-dollars” as she talks about the current dissension in Kashmir. She recounted her experiences with terrorists when both she and her husband were kidnapped and held hostage for over 45 days. They were hostages but the respect and ethos were pervasive in the way the abductors behaved with them. As Kashmiris, who grew up in Kashmir, the concept of religious identity was only introduced when the radicalization of the culture started. The power of empathy and compassion, our common heritage, and a resolve to allow Kashmiriyat be larger than hatred, defies every fracture that the world may try to create in the fabric of the Kashmiri society. Just like any other society, the Kashmiris also want to make progress as well. They want their children to be educated and have the best possible lives for themselves. They want the same opportunities that people have around the world have and have understood that terrorism is making a better life unviable for them.

The ground level support for terrorism is under duress or threat of life. So, what do the politicians do to fix this? Khem Lata Wakhlu doesn’t mince her words in blaming politicians for their vacillating loyalties. She is dismayed that nothing has been done or said by them that could lead to a viable solution to the on-going commotion. She berates them for not telling the truth for reasons of sounding too politically polarized. That, she feels, is harming the Kashmiris. She also is not impressed by people settled outside Kashmir for opining about the Kashmir solution from afar. She acknowledges that even within Kashmir there are key stakeholders who may be politicians, bureaucrats and law and order officials gaining monetarily and otherwise by keeping the unrest on a slow burn. People of Kashmir are fed up with corruption, favoritism, and nepotism. They want an end to this tumult and are willing to come forward to whistle blow the corrupt. She wants the politicians to now start preparing for a free and fair election in the Valley and other parts of the erstwhile state. A new wave of young activist politicians is now ready to jump into making sure that legislation works for their people. She argues that the old Kashmir’s ethos remains.

A Kashmiri Century: Portrait of a Society in Flux, HarperCollins, Pp 384, ISBN 978-9354223273

Follow us on Twitter @AlterVoices